Challenging Poem: Theories of Time and Space

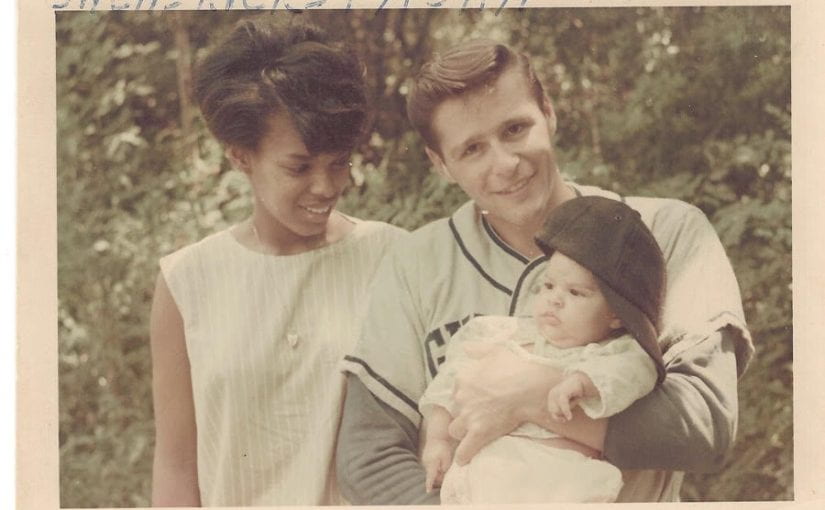

Natasha Trethewey’s “Theories of Time and Space” is challenging on a first read, mostly due to its layered meanings and very abstract ideas. At first, it seems like a straightforward poem about a road trip along the Gulf Coast, but the opening lines (“You can get there from here, though / there’s no going home”) makes it clear there’s a bigger picture, even though the reader does not yet understand it. Additionally, the poem’s title itself can be confusing, as it seems unrelated to this narrative of a road trip that Trethewey uses to get her ultimate point, that experiences are shaped by not only the physical worlds but our internal perceptions. Trethewey’s own experience growing up as a biracial child in a segregated South informs the poem’s exploration of how history, race, and personal memory intertwine, often creating many layers of meaning and emotion when looking back on memories like a road trip.

Accessible Poem: Graveyard Blues

Natasha Trethewey’s “Graveyard Blues” is relatively easy to understand compared to some of her other work, especially when you are aware of Trethewey’s personal history. It deals with themes of loss and memory through a very understandable setting: a graveyard. By using suce a universally understood setting, Trethewey creates an entry point for readers to contemplate complex themes of grief and memory and for herself to commemorate her mothers loss without the need for heavy interpretation or complex symbolism. The themes of grief and the permanence of loss are central to Trethewey’s own life, as her mother was murdered by her stepfather when Trethewey was only 19. This tragic event, which deeply affected her, is central to many of her works, including Graveyard Blues. Understanding Trethewey’s personal history helps the reader connect more deeply with the poem, as her own experiences with memory and mourning inform the speaker’s reflections on the dead. The poem’s simplicity allows readers to focus on its emotional content, making it accessible while exploring themes of memory, mortality, and remembrance.

“Just Right” Poem: Elegy [“I think by now the river must be thick”]

Natasha Trethewey’s poem “Elegy [“I think by now the river must be thick”]” strikes a perfect balance between accessibility and depth, making it a “just right” example of poetry. The poem discusses themes of loss, memory, and the passage of time through the narrative of a fishing trip, capturing the complex emotions that accompany mourning. The language is direct, but the meaning is hidden behind the narrative. Trethewey’s choice of imagery, such as the river becoming “thick” over time shows the slow accumulation and effects of grief and memory. This imagery is clear enough for readers to understand but it also invites deeper reflection on what it means for time to “thicken” and how loss changes our perception of it. Trethewey’s personal background enhances the impact of Elegy [“I think by now the river must be thick”]. The poem is deeply personal, rooted in her own experience of grief, especially the loss of her mother. Understanding Trethewey’s life and her engagement with themes of loss, race and memory provides greater insight into the poem’s emotional depth for Trethewey. The poem doesn’t just comment on her mother’s death but the collective memory of loss, shaped by history and race.

Additional Reading (and Watching) on Natasha Trethewey:

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/q-and-a/how-natasha-trethewey-remembers-her-mother